First, play the music as many times as you can

You must be quite familiar with the music. Knowing the song well entails not only understanding the primary melody and how each section changes, but also listening to all of the levels inside the music. For example, you may notice variations in the basic rhythmic framework at first, then pay attention to the ornamentation (all those little Dums and Taks that may not be noticeable straight away), then to what the violin says, then individually to qanun or oud, and so on. It doesn’t mean you have to choreograph your dance to every detail of the song, but knowing your music’s ins and outs opens up a world of options and cues for making your dance more intriguing. Instead of four straightforward hip drops, you might notice that a drummer added a fast tremolo on the third count, so here it is – you diversify your combo with an unexpected shimmy accent. You may want to highlight a violin passage at another point, while an accordion portion may be highlighted at another. All of this not only helps you create a more fascinating choreography, rather than repeating the same three-four moves, but it also helps you attract the audience’s attention.

Second, look up the lyrics’ translation.

Even if your recording lacks lyrics, make sure it isn’t simply an instrumental version of a well-known song. If the music originally included lyrics, you should keep them in mind even if the audio you’re using lacks a voice.

Why is it vital to know and understand a song’s lyrics?

To begin, it will offer you a notion of the overall mood: happy, sorrowful, poetic, and so on. It’s difficult to rely solely on “feel” in Arabic music: a melody can be quite joyous and energetic, but with some dramatic and heartbreaking sections.

Second, it can keep you out of a lot of embarrassing situations. Prayer songs or music with religious themes, for example, are probably not the greatest choice for a belly dance performance. Another example is contemporary shaabi music, in which singers frequently discuss drugs or harsh words. It may be fun to dance in a nightclub, but you should usually avoid utilizing such tracks in family-friendly restaurants or at a wedding.

Third, just like melody or drum embellishment, comprehending the lyrics provides a wealth of choreographic possibilities and cues. Your dance should not only represent the instrumental music or percussion, but also the voice and, more precisely, the lyrics. Of course, don’t go so far as to mimic every single phrase. Your objective is not to repeat precisely what the lyrics say, but to color it with your own feelings and artistic expression. For example, if a singer sings about falling in love with those gorgeous eyes, you can place your hand on your heart or your eyes: just one small detail to mirror the lyrics in your dance. And it can be a standalone movement, a layer on top of your shimmy or maya, or anything else that fits your artistic concept.

Third, begin by improvising and paying attention to your body.

Setting up a camera and documenting your dancing impulses and how your body naturally wants to move to a given tune may be quite beneficial, especially if you haven’t yet formed your choreographic memory. Even if you are an experienced choreographer, it can be difficult to repeat that wonderful combo that you somehow miraculously did only a second ago… Documenting your method is always beneficial. Always keep in mind that you are capturing a working process at this point, so there should be no rush to create a perfect piece/movement/combination right away. Otherwise, it could stifle your spontaneous creativity. Allow yourself to be liberated and experiment first. Later on, you’ll mold it more formally.

Fourth, accept that your initial draft will be imperfect.

Of course, miracles happen, and you might get it right immediately. However, most of the time, it will take X amount of modifications until your choreography is acceptable. Remember that even your first rewrite requires you to have a draft initially. So take the weight off your shoulders and do something, even if it’s only a basic marker, even if you have to skip a section of a song for the time being since nothing comes to mind. It makes no difference. You’ll return to those gaps later. A first draft is just that: a first draft. Nothing more, nothing less. You must have a foundation to develop from, and in the case of a first draft, “done” is preferable to “perfect.”

Fifth, before you begin, break down the song’s structure.

Dance is similar to storytelling. It is divided into three sections: the beginning, the development, and the conclusion. And each of these parts can be further subdivided. Listen to the full song and consider how you will construct your dance story, as well as what your focus will be on each portion. I’m not referring to the plot or anything like that; I’m referring to developing enthusiasm and energy.

You don’t have to start with everything. What are you going to do for the rest of the song if you load all of your moves and knowledge into the first minute? Also, imagine you’ve just met a new person at a party, and they’ve decided to tell you their entire bio before you’ve even finished shaking their hand. It would most likely frighten you… The same is true for your viewers. Take it gently at first and don’t overburden them.

Introduce fresh ideas one by one. Some sections will require travelling steps, while others may require floor work, with the next portion focusing on shimmies, and so forth. Consider your music and your interpretation of it, then consider how you may end your choreography on a high note. That’s why breaking down the music ahead of time may make choreography so much easier. Instead of worrying and thinking, “I need to do SOMETHING,” you’ll have a lot more specific focus for each segment of the dance.

Sixth.

Two magical maneuvers.

There are some moves that I utilize as aids when I get stuck on a particular area of the song. Shimmies and turns are involved. I’m not sure how to explain it logically, but at least one of them miraculously fits on practically any track, lol. I utilize this approach anytime I can’t think of anything yet still want to continue with the song. These are my assistants. Usually, by the time I finish my choreography and am ready to present it, such “shimmy” gaps have been replaced with something that better fits the music, although they are sometimes altered accordingly and remain in the final version. In any event, the next time you get stuck on a musical piece, see if shimmy or turns can help.

Seventh, look at other dancers’ work.

Examine footage of dancers you admire and note whatever combinations/movements piqued your interest. I’m not referring to copying someone else’s dance. That is completely unethical and goes against every basic creative ethic guideline. However, perhaps you found it interesting how that dancer placed her arm during a turn, or how she unexpectedly mixed two movements that you had never thought of combining…

These kind of diamonds could and should be used in your dance. This is not only a tool for expanding your movement vocabulary and challenging your body, but it is also a means to vary your dance and give you more creative ideas instead of repeating the same familiar movement patterns over and over. I also enjoy learning choreographies at various workshops. I may or may not follow through on such routines, but they always bring significant insights and different permutations that I can deposit into my “movement bank account.”

Eighth.

Work till you are able. Then push a little harder. But then you stop.

Not everyone is a genius who can choreograph all day. Even if you were inspired to work all day and complete the choreo in one set, that doesn’t guarantee that the next time will be the same. Choreographing is a physical as well as a conceptual process. It’s all too easy to become frustrated when our creativity flow becomes stalled and we begin to feel incapable of doing anything or not talented enough. Sometimes we only need to take a break and come back to it with new thoughts and renewed zeal.

Ninth, make sure you experiment with different directions, levels, and speeds.

It’s useful to question yourself, “Am I always facing the front?” and “How can I evenly address all sides of my performance area, as well as the center part?” Don’t forget about another option: facing back! When you display your hip or hair movement from the rear, it will look radically different than when you show it from the front! Furthermore, many costumes have really wonderful extravagant designs from all angles, so why hide half of their beauty?

It’s even easier to experiment with levels and speed. Instead of doing four conventional mayas, you may do them down and up. Alternatively, rather than being cautious and taking full two counts for a turn, you can perform the exercise quickly and then utilize the remainder of the phrase to calm down and stretch in a wonderful stance! Allow the photographer to capture a beautiful image while also making your dance more unexpected and intriguing.

Tenth.

Don’t just think about moves. Consider the audience’s interest.

At the end of the day, it is the audience’s experience that matters, not your technical ability. People’s attention is the most important factor in this regard. For example, if you are concentrating on intricate belly or hip technique during a given section of the dance, it may not be the best time to fling a little movement of the hands high above your head. People are unlikely to notice because their attention is focused on your belly and hips. You must discover a technique to smoothly transition from their emphasis on hips to your hands all the way up. Perhaps a reverse undulation, or any other movement, can aid in this case. However, draw people’s attention consciously. Don’t just pray that they pay attention to every aspect of your body all of the time!

Your own gaze is another effective weapon for controlling and directing the audience’s attention. People will immediately turn their heads to see what you are gazing at. So don’t dismiss your eyes and face. They are as much a part of your dance as your arms and legs, or, in our case, hips.

Eleventh.

Do not be afraid to solicit feedback.

Discuss the benefits of having a third-person view on your work-in-progress. It could be your teacher, a dance partner, or a friend. You might even consider taking a private class in person or through Skype with a dancer you admire to gain comments and suggestions on your choreography. Be receptive and ready to hear what they have to say. I would even go so far as to argue that you should be open to criticism. In this case, you don’t want someone to compliment your choreography talents, but rather to point out where they might be improved. Allow them to be completely honest and open because it will help YOU in the end. The preparation period is a safe moment to be vulnerable and confront your own flaws. It implies you’ll be more prepared for the primary presentation of your dance later on. Also, keep in mind that the final decision is always yours. You are not required to blindly follow the advice of your mentor. At the same time, the opportunity to hear the other person’s opinion can provide you with significant benefits because they are viewing your dance work from the perspective of the audience and may notice things that you as a creator do not.

Twelveth, practice how you intend to perform.

If you intend to perform your choreography with loose hair (like we do in 90% of belly dance events), start by choreographing it with your hair down. Later, while practice, you can put it up in a comfortable pony tail, but here are some reasons why you should start with your hair loose.

For starters, you will not limit your movement vocabulary. If you fix your hair and don’t feel its natural flow, you’ll most likely cut off all potential hair moves, which may be good if that’s your deliberate objective. I do it on purpose – or at least try to – knowing my affinity for particular hair accents, lol, but otherwise, why limit yourself?… Hair, like your arms and legs, is a part of your body. Use it carefully and to your advantage!

Second, have you ever seen a dancer fight her own hair while performing? Or just letting it smear all over her face for much the entire duration of the show? This is a typical problem for inexperienced dancers who don’t grasp the need of practising with a loose hair, as well as not include certain “recovery” periods that can help you handle your hair battle gracefully and without interfering with the integrity of your dance. For example, if you find that a specific movement or combination always causes your hair to finish all over the place throughout your choreography process, you might consider following up with a movement that will assist you take it away from your face. This way, it’s already built into your choreography, and you won’t have to worry about it later. In reality, this may be applied to any uncommon or hard feature of your dance, such as a short or open skirt, an extremely silky veil, a long sleeve on one side, and so on.

Thirteenth.

Prepare your costume ahead of time.

Of course, we don’t frequently confine our artistic souls to repeating the same dance in the same costume over and over, but remember that dancing in a narrow skirt is quite different than dancing in a wide one, with an altogether new set of possibilities and limitations. Depending on the complexity of my idea, I may work on my first draft while wearing a costume, or at the very least a skirt. I’d rather see if my outfit will allow me to do what I really want to do. Costumes may also be a terrific source of inspiration for choreographies because you can understand how to use them into the dance to your advantage.

Fourteenth.

The most remarkable aspects of your dancing

Although every moment of your dance is crucial, the beginning and finish of your dance will have the most impact on your audience’s experience.

The beginning is your introduction, your chance to make a good first impression and either attract or lose people’s attention. It’s the time when the audience is attracted by the novelty of a new dancer on stage, but also when they automatically decide whether or not to pay attention to the rest of your dance.

The conclusion, or final element of the dance, is their last impression, the moment they will most likely remember. I’m not talking about the aesthetic aspect, but rather the emotional one. It doesn’t matter if you had some kick-ass moments at the beginning of your dance but the rest of your performance was boring and low in intensity. People will not be left in awe after you depart the stage. The start of a dance establishes the tone and expectations, but you must develop your dance gradually, building up the excitement, and leaving your audience wanting more long after the act is over.

Fifteenth.

Perform the routine as many times as you can.

When you’re satisfied with a general sequence and don’t need to focus on what comes next, you can go into the details. You’ll notice that with each run, you’ll learn something new and wish to include modest changes into your fundamental structure. Maybe you’ll shift your head, or move your arm in a certain way, or hear an extra drum accent that you didn’t notice before… Practice time is when you add those delicious touches to your dance that showcase your unique artistic voice and make any movement sequence into a live dance creature with its own personality.

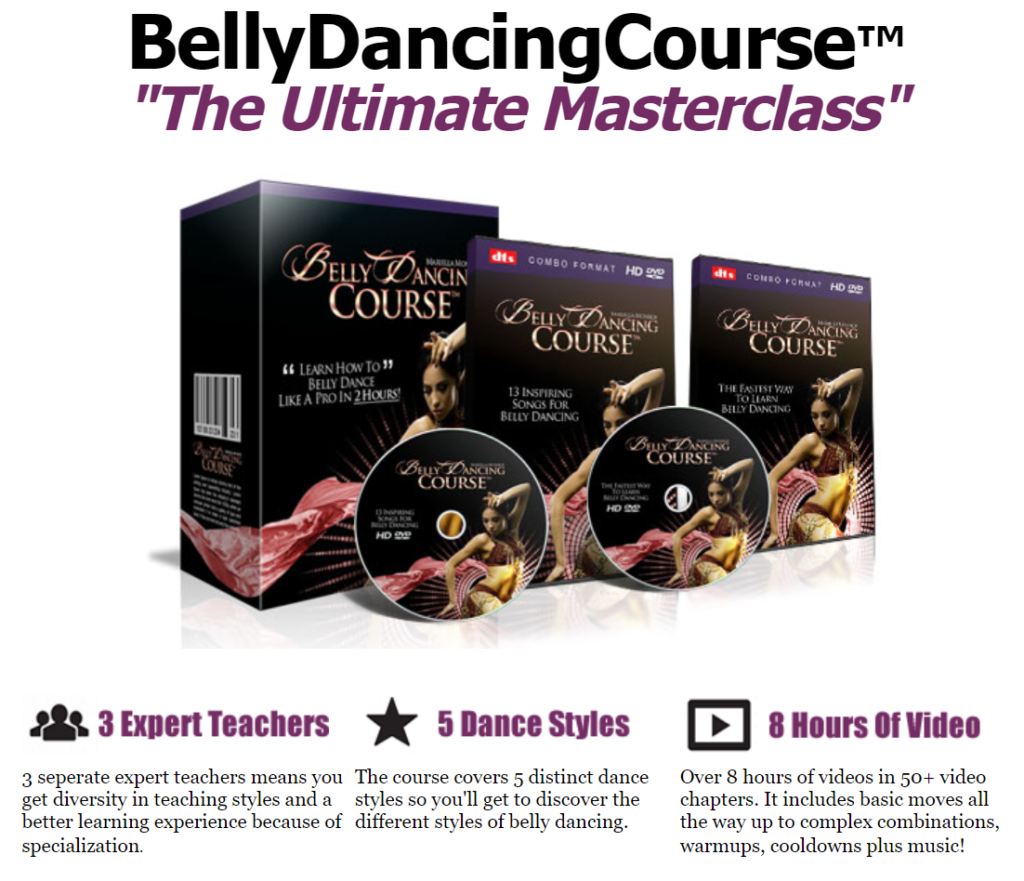

I hope you’ve found these choreography recommendations useful! If you want to take your belly dancing to the next level or even become a professional check out this course designed by professional belly dancers for anyone while you can! Click here